Parallel Library Services

The social practices of libraries

Libraries do much more than simply give access to knowledge; they produce sociality. The sharing of texts is a fundamentally social practice, bringing readers together in an exchange of positions, ideas, knowledge and know-how. But a library is more than just a collection of books and files. It is also the readers collected around them, and moments when they gather to share what they read. Collection; a common noun, an action, a collective noun. Sociality drives collections while performing publishing's feedback loop; making things public and also making publics.

Despite all this, the traditional model of the public library system, one inspired by the dream of a knowledge commons, is dying. Recent history has seen libraries closed all around the world with social distancing measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But both professional and amateur librarians have been predicting the downfall of the public library system since long before the pandemic hit.

In a 2014 interview, David Pearson, then Director of Culture, Heritage and Libraries at the City of London Corporation acknowledged that the core idea of a public library as "a place where a collection of books is available to borrow... is ultimately, a failing business model".[1] Pearson, a senior librarian and author of Books as History: The importance of books beyond their texts (2008), expresses dismay at the incursion of a corporate logic into public space; one that sees public services as businesses and libraries as simply places to keep books and files.

In a 2019 interview Dubravka Sekulić, architect, researcher and a librarian of the Memory of the World[2] project, vents her frustration at the commonly-held perception of physical libraries as "containers for books".[3] For Sekulić, this disregards the importance of physical libraries as places where the practices of reading together, annotating, organising and structuring are performed. She calls for ambitious responses to address the issue of "what is useful knowledge for people to understand what surrounds them? Or for example, what can help to understand the politics of knowledge distribution".[4]

Sekulić was not alone in her frustration. In 2015 she joined a long list of co-signatories[5] of the open letter 'In solidarity with Library Genesis and Sci-Hub'. The letter, published at custodians.online, on Sci-Hub and Library Genesis mirror sites, reports a disturbing power imbalance between publishers and researchers, closing with an impassioned call for sympathisers to come out of the shadows in an act of collective civil disobedience.

What a librarian does

In parallel with the decline of public libraries, a radical index of fugitive libraries and new initiatives offer re-interpretations of the role of the librarian and the social practices facilitated in its construction.

In Rotterdam's free reading room Leeszaal[6], both amateur and professional library practices meet. The library is staffed by volunteers, some with professional library training, many with only practical experience learned from working at Leeszaal. The books are not catalogued -- meaning that anyone can walk in, take a book, and walk out. Leeszaal maintains the socially-oriented library practices of distributing knowledge; running language and skill-building courses, delivering a public program of events, overseeing a busy lending library, offering use of their infrastructure (internet and computers) and a place for members of the local community to meet.

These projects and initiatives are aligned in their vision of the role of librarian. Librarianship is not centred within the objects or embedded individuals in the library, but instead within the social actions performed there.

The bootleg library: a particular, situated collection

A large part of the groundwork for Parallel Library Services comes from the research conducted through the bootleg library, a project I initiated during my graduation year at the Experimental Publishing (XPUB) Master Programme of the Piet Zwart Institute. The bootleg library began with an interest in the sociability that libraries produce, questions about the conditions that sustain a particular, situated library and the tasks to be performed within the shared role of librarian.

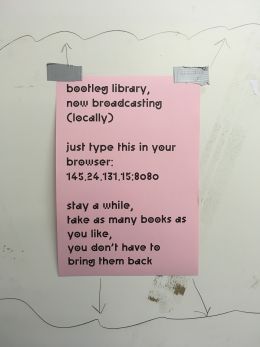

In the summer of 2019, I installed software on a computer in the XPUB studio, turned on a content server and immediately began distributing files over the local network.

I put up posters and laid out A6 cards to let others know about this shared resource of texts. I described it as intentionally small-scale, and local. Over the course of a year, the library developed in volume (but not scale), built by different but inter-connected publics.

Consisting of a travelling box of printed books, a digital library on a self-hosted webserver, and moments when readers meet to edit the collection by reading and writing together, the bootleg library is at once digital, physical and social. These are not separate, but overlapping elements, for example: bootlegged books that began as digital files, digital services hosted on physical hardware, social exchanges facilitated by software, and so on.

Bootleg library sessions[7] were accompanied by small groups of readers, the printed collection and the digital collection. We took notes, using A6 index cards and the collaborative text editor Etherpad[8].

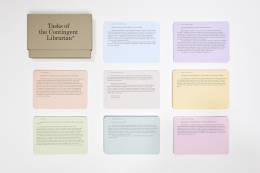

This documentation eventually became part of a text titled Tasks of the Contingent Librarian, an index of actions (e.g. including/excluding, diversifying through use, reprinting, making it public/keeping it private, annotating etc.) described in direct relation to the practice of the bootleg library. It is a text written together, layered in inter-dependencies.

The first printed version of this text is published by the Amsterdam art centre de Appel, my contribution to their exhibition/publication 'This may or may not be a true story or lesson in resistance'. Each action is described on one side of a printed card, with accompanying images and references on the reverse. Readers navigate through the text, "determining what to keep or discard, what to edit or leave as is... (to become) ...the author of the sequence, connections and hierarchy between tasks"[9].

The Tasks are published in many digital contexts with slightly varying content, interface and affordances; a dedicated website, Library of Contingencies*, is one of many digital versions of the same text; but one that exploits selectable and hyperlinked text, including copy/paste~able code snippets and workflows from the practice of the bootleg library, indexed alongside corresponding actions.

Contingent librarianship

Contingent librarianship is a collective practice of discovering, defining, documenting and administering actions that support social infrastructure. It uses hands-on experimentation with tools and methods to interface with knowledge structures and distribution systems. It supports open access to knowledge and collaborative authorship. It acknowledges the relationship between technical, conceptual and ontological processes and that there is value in our different positions and situated knowledges. Contingent librarianship is shorthand for a multitude of ancillary actions which are catalogued, shared and practiced.

The practice of contingent librarianship is always in relation to others. Our dependencies extend beyond technical software requirements; we are part of an inter-connected network of peers, collaborators and correspondents.

The case for self-managed social infrastructure

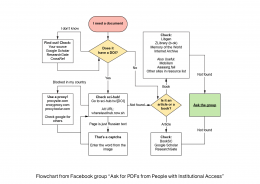

Research cultures rely on open access to texts and the social infrastructure that a library provides. Recent historical events have been met with an acceleration in calls for resources; software, files, documents and texts that support much-needed social infrastructure in a time of social distancing. These calls often come from beyond skilled and privileged communities, where many people lack the technical know-how, time and resources to host their own infrastructure. They depend on extractive tech services provided by companies such as Google, Facebook and Microsoft, which profit from selling on user's personal information and data. Others may be able to use so-called "shadow libraries" such as Library Genesis, monoskop.org or aaaaarg.fail; but always with the fear that these resources will suddenly disappear, or that sharing texts will make them vulnerable to incrimination.

The bootleg library demonstrated that setting up and organising a shared library is certainly achievable on a reasonable budget, with the right resources, time and know-how. Self-managing infrastructure empowers communities to maintain their integrity by protecting their data, and gives them the opportunity to express solidarity[10] with others by sharing documentation in the form of not just source files, but also descriptions and narratives that were part of its creation.

One, or many libraries, in parallel

In December 2020 I was invited to organise an online workshop at the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image (CSNI), a London-based research unit attached to the University of London Southbank. In this one-day "Parallel Library" workshop, participants formed a library using open-source tools, together deciding on its content, technical setup, classification system and ontology. The value of having a self-hosted library was proven in the enthusiasm, speed and ease with which it was established and filled with uploaded texts, hand-written metadata and annotations. Knowledge and know-how were accumulated rapidly through the one-to-one level of communication between participants; enabling questions, suggestions and modifications to be made directly and immediately.

It quickly became obvious that this workshop provided the beginnings of an iterable model that could be of great use to not only research cultures, but also to other communities where resources and technical skills were lacking; ones where such social infrastructure could assist. I began to think of initiating a service, comprised of ways knowledge and know-how could be freely distributed -- my own and that which was openly shared with me.

But one day is not enough. At the end of the workshop, it was clear that what was needed was time and resources to develop the model further. For a library to sustain itself, a critical mass of dedicated readers must be first established. A library depends on text produced by readers; publications, annotations, correspondence, metadata, software, et cetera. This comes with regular meetings and interactions between readers in the social space of text; editing the collection. And ultimately, the practice of contingent librarianship is far more important than simply talking about it.

Simon Browne, Rotterdam 2021

- ↑ Pearson, D. Interview with David Pearson, in 'Bookspace; Collected Essays on Libraries', London:Inland Editions, 2014, pp12-18

- ↑ https://memoryoftheworld.org

- ↑ XPUB, Interview with Dubravka Sekulić in The Library Is Open, Rotterdam: Piet Zwart Institute (XPUB Special Issue 09), Jul 2019, pp 46-50

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Dušan Barok, Josephine Berry, Bodó Balázs, Sean Dockray, Kenneth Goldsmith, Anthony Iles, Lawrence Liang, Sebastian Lütgert, Pauline van Mourik Broekman, Marcell Mars, spideralex, Tomislav Medak, and Femke Snelting

- ↑ https://leeszaalrotterdamwest.nl

- ↑ Bootleg library sessions were held in person and online at Piet Zwart Institute (XPUB, Lens-Based and MFA programs), Onomatopee in Eindhoven, Varia in Rotterdam's south and the Art Meets Radical Openness (AMRO) 2020 festival in Linz, Austria.

- ↑ https://etherpad.org

- ↑ Browne, S., Tasks of the Contingent Librarian, de Appel, Amsterdam, 2020

- ↑ https://vvvvvvaria.org/etherpump/p/digital-solidarity-networks.raw.html